TikTok as an Emergent "Co-Creational" Music Marketing Technology

*Originally submitted May 3rd, 2020 for the Sociology of Music course at the University of Virginia

Introduction

In 2014, two Chinese entrepreneurs launched the lip-syncing app Musical.ly, which gained hundreds of millions of followers over the coming years. In 2017, multi-billion-dollar Chinese corporation ByteDance purchased Musical.ly for $1 billion, and merged the app with their own similar app, TikTok. Today, the TikTok app has been downloaded more than 2 billion times (Leight, 2020; Schwedel, 2018). In this paper, I will explore TikTok as a novel music marketing technology through various frameworks, and contextualize my findings within the history of music marketing, as well as within the existing social media landscape. I will apply Appel et al.’s (2020) “Immediate Future” framework, and Gamble and Gilmore’s (2013) “Co-Creational Marketing” framework. Finally, I will discuss the impact TikTok has had on music production and sales, potential dangers of the app, and suggest future research.

Historical Overview of Music Marketing

In the late 19th century, mass distribution of music was done via written “sheet music” (Martin, 1995), and later “song pluggers” were hired by music publishers to promote their songs and “persuade entertainers to use their material,” (Ogden et al., 2011). The invention of the phonograph replaced sheet music as the popular way to consume music, and the phonograph was replaced by the radio in the 1920s. In order to monetize, radio stations sold airtime and implemented “on-air advertising” (Dominick, 1996). Music became a “mass consumable product” in the 20th century, and channels of distribution included live performances, newspapers, sheet music, and more (Ogden et al., 2011). In the 1930s, the long-standing business model for record production and distribution began, and record labels began implementing advertising campaigns to promote records, which were sold at physical retail locations. These ad campaigns included radio promotion, publicity in publications, and live performances (Ogden et al., 2011). World War II drove more listeners to radio, doubling advertising dollars between 1940 and 1945 (Ogden et al., 2011), and when television emerged in the 1940s, popular radio shows migrated. Programs like the Ed Sullivan Show gave lesser-known musicians a platform (Fink, 1989). In the 1950s, the Top 40 format was established at radio, and showcased the most popular singles at the time. The popularity of these singles led to the creation of 45s, and the stereo record was born in 1957. During this time, marketing turned toward a “sales orientation,” which continued into the early 1970s; this involved salespeople going door to door and pushing products (Ogden et al., 2011). Cassette tapes were born in 1963, followed by eight-tracks in 1965. These new technologies meant that people would re-purchase music they previously owned on older technologies. MTV debuted on Television in 1981, and CDs followed, which again contributed to this “re-purchasing behavior” (Ogden et al., 2011). This time also birthed the “marketing concept,” which was much more focused on consumers wants and needs (Ogden et al., 2011). The music industry was at an all-time high before Shawn Fanning created Napster—the first free online MP3 file-sharing site—in 1999 (Ogden et al., 2011). The iPod was released in 2001, and the early aughts saw a major increase in pre-existing channels of music distribution. These included in-store appearances by artists, PR in publications, guerilla advertising in cities, music videos, television and radio appearances, movie features, touring, and merchandise. However, “In today’s world…record companies are losing some control over their industry as the conventional business models of the past are no longer as effective thanks in large part to the Internet,” (Ogden et al., 2011; Thall, 2002).

Social Platforms as Marketing Tools

Historically, word-of-mouth (WOM) marketing has been found to be incredibly effective and valuable to marketers (Appel et al., 2011; Babic Rosario, 2016; Bruno, 2011; Ogden et al., 2011). Social media is an online worth-of-mouth marketing form, or eWOM (Appel et al., 2020). Through these channels, marketing has come to involve “technology and a greater degree of personalization and value creation,” (Ogden et al., 2011). Before TikTok, Twitter—established in 2006—was viewed as the most promising social platform for music marketing (Bruno, 2011; Cosimato, 2019). A 2019 study by Cosimato surveyed a multitude of social media platforms and web pages (such as Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram) to predict Billboard 200 Chart ranking of forthcoming albums. Cosimato (2019) found that Twitter was the most significant and accurate predictor of future Billboard success, as measured by tweet rate, negative sentiment of the tweets, and retweet rate. And while formal music promotion has been found to be effective but inconsistent, regular WOM sharing of music on the platform does well (Bruno, 2011). Twitter is also notable for its ability to foster “para-social” relationship between artists and fans. These “para-social” relationships typically take place between a “celebrity” and a “fan,” and occur when one party, usually the fan, invests time, effort, and emotional interest into the relationship, and the other party, usually the celebrity, is unaware of the first party’s existence. These “para-social” relationships can lead to “quasi-social” interactions, which are mediated interactions between these two parties that usually occur through a form of mass media, such as a celebrity responding to a fan’s tweet (Turner, 2013).

Framework 1: Appel et al.’s (2020) “Immediate Future” Framework

In Appel et al.’s 2020 study, the researchers identified three frameworks for the future of social media in marketing. They state the two key aspects of the current social media landscape; the first is major versus minor platforms (established versus emerging), and the second is use cases, which describes how various kinds of people and organizations are using these technologies and for what purposes. The researchers identified three purposes of social media: digitally communicating and socializing with known others, such as family and friends, doing the same but with unknown others who share common interests, and accessing and contributing to digital content such as news, gossip, and user-generated product reviews. The three frameworks detail social media marketing in the immediate future, the near future, and the far future. For my research, I focused only on the first framework of the immediate future. Each framework focuses on three aspects: the individual, the firms, and public policy. The individual aspect of the immediate future is described as “omni-social presence” (Appel et al., 2020). The authors describe this as the phenomenon of social media “shaping culture itself.” In Appel et al.’s (2020) example, “YouTube influencers are now cultural icons…Social media’s influence is hardly restricted to the ‘online’ world…but is rather consistently shaping cultural artifacts…that transcend its traditional boundaries,” (p. 82). The firms aspect of the immediate future highlights “the rise of influencers.” Traditional celebrities with big followings are good for marketing, but expensive, and brands have started to rely on “micro-influencers” who are less known, but have “strong and enthusiastic followings.” The use of micro-influencers in marketing is perceived as more “trustworthy” and “credible” (Appel et al., 2020). Finally, the public policy aspect focuses on trust and privacy concerns, such as data mining.

Framework 2: Gamble and Gilmore’s (2013) “Co-Creational Marketing” Typologies

Gamble and Gilmore (2013) identify five co-creational marketing typologies and how they have been applied to the music industry. Gamble and Gilmore (2013) quote Baym and Burnett (2009) in asserting, “Spreading the word about new music is enacted along a spectrum that ranges from very low to very intense investment. Together these fans create an international presence far beyond what labels or bands could attain,” (p. 437). These five typologies are presented on a matrix of an inverse relationship between consumer and organizational involvement and control (see Appendix A).

Appendix A

Co-Creational Marketing Matrix from Gamble and Gilmore’s (2013) Review

The first typology is “viral marketing” and has the lowest consumer control and involvement, with the highest organizational control and involvement (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). In viral marketing, the artist or organization creates a piece of content hoping that it will “go viral” and be shared organically by consumers, therefore generating “buzz” (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). Ferguson (2008) suggests that viral marketing has become the “defining marketing trend of the decade.” Gamble and Gilmore (2013) identify viral music videos as a music industry example of viral marketing. The second typology is “sponsored user-generated brand (UGB) marketing” (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). UGB campaigns are still “initiated and regulated” by the organization, but actively ask for consumer contributions through channels like blogs, contests, and voting. The organization sets the parameters for the content to be submitted by consumers, as they want it to remain in-line with the brand’s “image” and “identity” (Burmann, 2010). The third typology is “user-generated content (UGC) marketing.” Here, the consumer begins to act as a “broadcaster” (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). TikTok, like Twitter and Facebook, is a UGC platform. This typology can take many forms: “blogs, mash-ups, online reviews, peer-to-peer Q&As, video clips, social networks, avatars” and more (Gray, 2007, p. 23). Baym and Burnett (2009) state that “Voluntary fan effort can be seen throughout the music industry, and speaks to the fundamental changes that global industry is experiencing as the music business increasingly shifts to digital formats,” (p. 434). The fourth typology shifts towards greater consumer control and much less organizational control. In “vigilante marketing,” consumers are seen as “social broadcasters” (Simon, 2006). The consumers are usually producing content “without the organization’s knowledge or consent” (Berthon et al., 2008), and are doing so because of a certain “loyalty” or “devotion” to the brand (Muñiz and Schau, 2007). Because there is very little organizational control in vigilante marketing, there is a risk that the brand could be presented negatively (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). One music industry example of vigilante marketing is fan-created music videos. The final typology, “prosumer marketing,” sees the most consumer control. The concept of the prosumer (a combination of “producer” and “consumer”) was first identified in 1980, but has seen a resurgence in the digital age (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). In this practice, the consumer becomes “involved in the design and manufacture of products and services” (Konczal, 2008, p. 22). Today, prosumers represent “one of the fastest growing and highest value segments in today’s communications market,” (Konczal, 2008, p. 23). Music industry examples include fan contributions to song lyrics (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013).

How and Where Music is Used on TikTok

For my research, I spent multiple hours daily collecting data from my “feed” in TikTok, or the “For You Page” (FYP). I recorded data from February 24th, 2020 to April 29th, 2020. Through my observations, I identified what I believed were the most prominent uses of music on the app. Unlike other apps like Twitter and Instagram, every piece of content (video) uploaded to TikTok is accompanied by audio, or what the app categorizes as a “sound.” This format organically encourages the use of music, and TikTok has a library of licensed “sounds” and snippets of songs that users can choose from. Most videos on the platform are 15 seconds, but can run up to 60 seconds. Songs seemed to be chosen based on how literally lyrics could translate to a video concept, or the ability to dance to it. The most popular uses of music on TikTok that I observed were via: sponsored or promoted advertisements from organizations, remixes created and shared by consumers, UGB and UGC videos from popular creators and influencers, the re-circulation of old songs, the creation of a new “dance trend,” and through artist promotion on their personal pages. Nick Sylvester, producer of “Old Town Road,” explains that music is always adapting to new technologies; “Technology has always changed the kinds of records that are made…[TikTok] is showing that people want to do more with music than just listen to it. They want to interact with it; they want to touch it,” (Harris, 2020).

Co-Creational Marketing Within TikTok

To an extent, nearly everything is posted on TikTok with the hopes of achieving virality. One highly visible example of viral marketing on TikTok is Drake’s most recent single, “Toosie Slide.” In late march, before the single was released, Drake commissioned viral hip-hop dancer Toosie to post a clip of himself performing the simple dance to a short snippet of the song (Caramanica, 2020). Shortly after, the snippet went viral on TikTok, with thousands of accounts posting their own #ToosieSlide video. The #ToosieSlide hashtag currently has 4.3 billion views across its videos, and the official “Toosie Slide” by Drake sound has been used in nearly 3 million videos. The single was released in the midst of its viral TikTok fame, and debuted at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

TikTok, following platforms like Instagram, allows users to post content that is sponsored user-generated branded content, or UGB. A common practice of UGB on TikTok is for organizations to pay a popular creator or micro-influencer to promote a song, but allow the creator to come up with original content for the promotion (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). One user, Kio Cyr (@kiocyrrr), has 5.4 million followers and shared that he receives up to $3000 to promote one song (Yurieff, 2020). Three popular TikTok influencers were paid to promote the “Trolls World Tour” by choreographing a dance to “The Other Side (from Trolls World Tour)” by SZA and Justin Timberlake. @yodelinghaley (1.5 million followers), creator of the “Say So” viral dance, choreographed and posted the dance on April 7th. @addisonrae (37.2 million followers) and @mads.yo (7.9 million followers) recreated the dance and posted their own videos. These videos have a combined 11 million views.

All content on TikTok could technically be defined as “user-generated content,” being that it is a UGC platform. However, not all of the UGC on the platform is intended as marketing. On March 23rd, 2020, Lauv (@lauvsongs) posted a video on his personal TikTok account of himself dancing to his recent single, “Modern Loneliness.” In the caption, he asked people to “duet w this if you wanna be in the music video.” On TikTok, users can “duet” videos, meaning that they record their own video alongside the original video. The official “Modern Loneliness” sound has now been used in over 10,700 videos, yet only a handful were chosen by Lauv to appear in the official “Modern Loneliness” music video. By using an interactive call to action, Lauv allowed his fans to generate content for his own music video, as well as promote the song across the app.

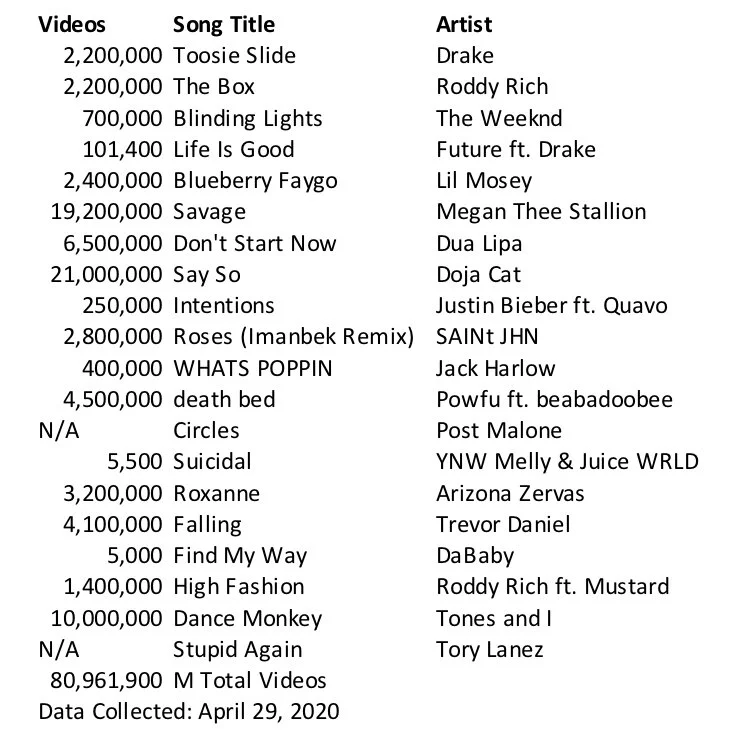

Vigilante marketing seems to be the most prominent form of music use on TikTok. In this typology, consumers are not necessarily being asked by the organization to create content, and are assuming full creative control (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). When TikTok users use a song for a new dance or trend, remix existing songs, or simply use a song as the soundtrack to a video, they are engaging in vigilante marketing. Like Twitter, content of this nature that purely seems to be eWOM is the most successful (Bruno, 2011). I surveyed the top 20 songs of the Billboard Streaming chart (songs performing the best on streaming) for the week of April 25th, 2020, and found that a total 80.96 million videos were created across these top 20 streaming songs (see Appendix B).

Appendix B

Top 20 Billboard Streaming Singles Metadata

After further research, I found that nearly all twenty songs were associated with a popular TikTok dance trend. The few that were not associated with a dance trend were either used for a different trend, or had been used by the biggest influencers on the platform, such as Charli D’Amelio (@charlidamelio), a 16-year-old girl with 52.3 million followers. This speaks to the rise of influencers and their omni-social presence. There appears to be a strong correlation between a song’s performance on streaming services and it being used by a popular creator. This suggests that these “social broadcasters” (Simon, 2006) on TikTok, often teenagers, have the ability to shape culture beyond the app. This same practice has also worked to repurpose “old” songs (Lindsay, 2020; Yurieff, 2020). This was the case for Matthew Wilder’s “Break My Stride,” which was originally released in 1980. The song became attached to a viral trend in which users posted videos acting out the lyrics, and nearly 800,000 videos were made to the 15-second clip of the song. The #BreakMyStride hashtag has been viewed 170.9 million times across videos. Because of this, the 40-year-old song entered Spotify’s Viral 50 playlist in both the U.S. and U.K., and Apple Music’s Top 100 chart in twenty-one countries (Yurieff, 2020).

TikTok offers unique opportunities for consumers to become prosumers. Drawing on research by Simon (2006), Gamble and Gilmore (2013) suggest that these social broadcasters’ “extensive use of UGC practices may actually lead to the production of both new music products and commercial opportunities.” One example of this is users on TikTok creating remixes or “songs” that become “new music products.” TikTok comedian Curtis Roach (1.5 million followers) uploaded a video on March 4th of himself lying on the ground, using his fist to create a beat to rap over. He rapped a simple verse about being “Bored in the house and I’m in the house bored.” The video has been viewed 36.2 million times, and rapper Tyga created his own video using the sound (which has been used over 4 million times). Three weeks later, Roach and Tyga released an official, full-length version of “Bored in the House” across all streaming services. On October 1st, user @mattsmixtape posted a video of a remix he made of mxmtoon’s “Prom Dress,” in which he added in adlibs from Lil Jon. The video accumulated over 1.2 million views, and this remixed version has been used in nearly 50,000 videos. On April 19th, mxmtoon, on her personal TikTok account (@mxmtoon), posted a video of her singing along to “Prom Dress,” cross-cut with videos of Lil Jon singing the adlibs that @mattsmixtape had imagined. In her caption, mxmtoon wrote, “thank you @liljon for making ‘prom dress’ a thousand times better!! special shoutout to @mattsmixtape for making this idea come to life.”

TikTok Music Use Outside of the Co-Creational Model

Two instances of music use on the platform were widespread, but did not necessarily fall neatly into one of the five typologies of co-creational marketing. The first is promoted advertisements. These “in-feed social ads” (Chang et al., 2019) follow a similar format to branded or promoted content on other social platforms. Chang et al. (2019) paraphase Barcelos et al. (2018) by explaining that in-feed ads are presented to users as integrated into the platform seamlessly and look like content from any of their friends. Consumers interact with these branded ads similarly to content from friends by “liking, commenting, and sharing” (Kwon and Sung, 2011). Between February 24th, 2020, and April 29th, 2020, the TikTok algorithm integrated 57 promoted, music-related ads into my FYP (see Appendix C).

Appendix C

FYP Promoted Ads Metadata

These 57 ads totaled a combined 300 million views. The ads are formatted like any other TikTok on the FYP, but contain a “promoted” or “sponsored” button, to indicate that the viewer is receiving paid promotional content. Viewers are typically able to like, comment, and share these videos. This practice aligns the most with viral marketing, in that it is predominantly controlled by the organization, and relies on consumers to pass along the content (Gamble and Gilmore, 2013). However, the actual content of the videos is not necessarily intended to “go viral,” but rather serves as a traditional ad, promoting an artist’s new single, album, or music video. These videos were oftentimes vertical versions of existing music videos, or promotional videos created by labels and creative teams. Some ads linked the user to a sound to use within TikTok, and encouraged users to use it, but most linked users to streaming platforms or YouTube videos.

The other feature that does not occupy one particular typology is artists promoting their songs through their own pages, although the practice borrows elements from both viral marketing and UGC. In one example, artist Olivia O’Brien (@oliviagobrien) posted a video her personal account dancing to her latest release “Josslyn.” Because the video performed well, her manager asked that she make another. In the video, she rolls her eyes and sarcastically gives the middle finger to her manager, set to “Josslyn.” It is her most viewed video, with 4.6 million views. “Josslyn” has been used in 48,500 videos across the app. She is creating her own content (UGC) to promote her own music, and allowing her followers to interact with the song and her videos (viral). In another example, artist Alexander23 (@alexander23lol) made videos with his unreleased song (“IDK You Yet”) to create fanfare before its official release. Caramanica (2020) explains that, for lesser known artists, TikTok can be a way to “gauge potential interest in an idea, a sound or a lyric, before committing resources to it.” Alexander23’s initial video (posted March 29th) with the snippet of the unreleased song accumulated over 1.3 million views, and since its release four weeks ago, “IDK You Yet” has been used in over 58,000 videos on the app. In using viral marketing and UGC strategies, Alexander23 was able to get audience feedback and create “buzz” for his single before its official release.

Effects on Music Production and Industry

The ubiquitous use of music on TikTok has not only demonstrated many co-creational marketing strategies, but it has also seemingly affected how music is produced and how the industry operates. To build songs for virality, songs have become more focused on interactive elements and the inclusion of a “calling card” (Harris, 2020). One example of this is Roddy Rich’s “The Box,” which has been used in over 4 million TikTok videos and is widely recognized by its signature “creaking” sound. “The Box” peaked at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100. Songs have also gotten shorter and become more focused on including a “viral component” (Yeung, 2019). Yeung (2019) found that, “According to analysis by Quartz, the average song on the Billboard Hot 100 fell by 20 seconds between 2013 and 2018, down to 3 minutes 20 seconds. With TikTok, that process has accelerated.” The original version of “Old Town Road” by Lil Nas X stands at just 1 minute 53 seconds. The song is now the longest #1 single in Hot 100 history, spending 17 weeks in the top spot. The success of the song on TikTok spurred six remixes to keep the “buzz” alive.

The success and virality of songs on TikTok spurring remixes extends to other songs, too. TikTok user @yodelinghaley (1.5 million followers) created a dance to Doja Cat’s “Say So” in an original video posted on December 11th, 2019. The original video has 6.9 million views, and over 20 million videos have been made to “Say So” on TikTok. @yodelinghaley then appeared in the “Say So” music video with Doja Cat, and both performed the dance together. On April 29th, 2020, Doja Cat teased that a remix of “Say So” with Nicki Minaj would be coming soon. “Say So” peaked at number 5 on the Billboard Hot 100, and remains in that spot. The remix with Nicki Minaj has the potential to boost its chart position (Kelley, 2020). Similarly, TikTok user @keke.janajah (866,200 followers) posted an original dance to “Savage” by Megan Thee Stallion on March 10th, 2019. Her original video has 27.8 million views, and over 19 million videos have been created to “Savage” on TikTok. Megan Thee Stallion released a “Savage” remix with Beyoncé, whose verse includes the line, “Hips TikTok when I dance.” The song peaked at number 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 the week of April 18th, 2020, and the remix has the potential to boost this position (Kelley, 2020).

Artists have started specifically “name-dropping” famous TikTokers for a shot at virality. Artist The Kid Laroi created a short clip of a song with the lyric, “I need a bad bitch, Addison Rae/Shorty the baddest,” mentioning major TikTok influencer Addison Rae (37.2 million followers). Addison created a video using the sound, and it has now been used in over 130,000 TikTok videos. At the time that Addison used the sound, The Kid Laroi admitted it was not even a fully fleshed-out song. He turned it into a full song only after Addison caused it go to viral (Caramanica, 2020).

Potential and Active Dangers of TikTok

TikTok has been prominent in the news for the future of the app’s relationship with the major labels. In order for songs to be available to users on TikTok, the major labels must agree to license them to the app. Todd Schefflin, Head of Global Music Development at ByteDance, argues that, “TikTok is for short video creation and viewing, and is simply not a product for pure music consumption that requires a label’s entire collection,” (Shotwell, 2019). Jonathan Strauss, co-founder and CEO of Create Music Group, explains that views on TikTok do not impact royalty payouts to music groups, “Royalties get paid through posts—every single new creation that occurs, that’s the amount that gets paid out to the rights holders…It doesn’t matter if a post gets a million views or not,” (Leight, 2020). Currently, the three major labels are in re-negotiations to reach a licensing agreement (Leight, 2020; Shotwell, 2019).

To echo Appel et al.’s (2020) public policy prediction, TikTok has encountered trust and privacy concerns, with the United States officially putting the app under national review in 2019 for selling user data to China (Isaac et al., 2019). Another concern of the app is that they are owned by a multi-billion-dollar Chinese corporation, which has the ability to control trends and data from the back end (Isaac et al., 2020; Leight, 2020). Lastly, the app has struggled with obtaining an older audience. Artist mxmtoon, who has achieved her fair share of TikTok viral fame, claims, “There’s an image of TikTok being cringier comedy for younger individuals in middle school,” (Leight, 2020). Other dangers of TikTok are a promising area for future research.

Conclusion

This paper examines TikTok as a relatively new social media platform and the ways in which it has become an emergent music marketing tool. In order to analyze the ways music marketing occurs on the app, I applied two frameworks. Appel et al.’s (2020) framework provided important overarching concepts that have and will emerge in the “immediate future” of social media marketing, such as “omni-social presence” and “the rise of influencers.” They also brought up the issue of “trust and privacy concerns”, which are at the forefront of discussions surrounding TikTok (Isaac et al., 2019). I used Gamble and Gilmore’s (2013) five typologies of “co-creational marketing” as they apply to the music industry, and provided examples from TikTok for each of the five typologies. I also provided examples of music marketing and promotion within the app that perhaps challenge this framework. I demonstrated that the success of songs on TikTok has impacted the music industry and the production of songs, for example making them both shorter and more focused on “interactive” qualities (Yeung, 2019; Harris, 2020). Lastly, I briefly discussed potential and active dangers of TikTok. Many of these relate to Appel et al.’s (2020) “trust and privacy concerns,” with TikTok coming under “national security review” in the United States concerning the selling of data to China (Isaac et al., 2019). In the future, the app will have to find ways to reach an agreement with the major labels regarding licensing, and successfully attract an older audience that appeals to marketers. As TikTok is so new in the social media space compared to its tech-giant predecessors, there is limited research available, and certainly further research should be conducted on the relationship between TikTok and the music industry, as well as social, political and legal concerns surrounding the app.

References

Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2020). The Future of Social Media in Marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 79 - 95.

Barcelos, R. H., Dantas, D. C., & Sénécal, S. (2018). Watch your tone: how a brand's tone of voice on social media influences consumer responses. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 41, 60–80.

Battan, C., Petrusich, A., & Hsu, H. (2020, February 24). The TikTok-Ready Sounds of Beach Bunny. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/03/02/the-tiktok-ready-sounds-of-beach- bunny

Baym, N.K. and Burnett, R. (2009), “Amateur experts: international fan labour in Swedish independent music”, International Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol. 12 No. 5, pp. 433- 449.

Berthon, P., Pitt, L. and Campbell, C. (2008), “Ad lib: when customers create the ad”, California Management Review, Vol. 50 No. 4, pp. 6-30.

Bruno, A. (2013, July 19). Twitter, music and monetization. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/1178779/twitter-music-and-monetization

Burmann, C. (2010). A Call for ‘User-Generated Branding’. Journal of Brand Management, 18(1), 1 - 4.

Caramanica, J. (2020, April 7). It's a TikTok! No, It's a Song! Drake and the Viral Feedback Loop. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/arts/music/drake-toosie-slide-tiktok.html

Chang, Y., Li, Y., Yan, J., & Kumar, V. (2019). Getting More Likes: The Impact of Narrative Person and Brand Image on Customer–brand Interactions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(6), 1027 - 1045.

Cosimato, A., De Prisco, R., Guarino, A., Malandrino, D., Lettieri, N., Sorrentino, G., & Zaccagnino, R. (2019). The Conundrum of Success in Music: Playing It or Talking About It?. IEEE Access, Access, IEEE, 7, 123289 - 123298.

Dominick, J. R. (1996). The Dynamics of Mass Communication (5th ed.). New York: McGraw- Hill.

Ferguson, R. (2008), “Word of mouth and viral marketing: taking the temperature of the hottest trends in marketing”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 179-182.

Fink, M. (1989). Inside the Music Business: Music in Contemporary Life. New York: Schirmer Books.

Gamble, J., & Gilmore, A. (2013). A New Era of Consumer Marketing? : An Application of Co- Creational Marketing in the Music Industry. European Journal of Marketing, 47(11/12), 1859 - 1888.

Gray, R. (2007), “The perfect guest”, Campaign (UK), 8 June, pp. 23-24.

Harris, M. (2020, February 3). A music producer just explained how to make your song go viral on TikTok. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from http://www.insider.com/tiktok-music-producer- nick-sylvester-perfect-viral-song-2020-1

Isaac, M., Nicas, J., & Swanson, A. (2019, November 1). TikTok Said to Be Under National Security Review. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/01/technology/tiktok-national-security-review.html

Kelley, C. (2020, April 30). The Dawn Of TikTok Remixes Is Here Thanks To Beyoncé And Nicki Minaj. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/caitlinkelley/2020/04/29/the-dawn-of-tiktok-remixes-is- here-thanks-to-beyonc-and-nicki-minaj/#358f80746cf7

Kubacki, K., & Croft, R. (2004). Mass Marketing, Music, and Morality. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(5-6), 577 - 590.

Konczal, J. (2008), “Identifying, knowing and retaining your customers: the ‘prosumer’”, Customer Interaction Solutions, Vol. 26 No. 11, pp. 22-23.

Kwon, E. S., & Sung, Y. (2011). Follow me! Global marketers’ Twitter use. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 12(1), 4–16.

Leight, E. (2020, January 16). 'If You Can Get Famous Easily, You're Gonna Do It': How TikTok Took Over Music. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from http://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/tiktok-video-app-growth-867587/.

Lindsay, K. (2020, March 24). The Songs You're Hearing All Over TikTok In 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from http://www.refinery29.com/en-ca/2020/02/9457735/tiktok-songs- 2020-playlist

Martin, P. J. (1995). Sounds and Society: Themes in the Sociology of Music. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press.

Muñiz, A.M. Jr and Schau, H.J. (2007), “Vigilante marketing and the consumer-created communications”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 35-50.

Ogden, J. R., Ogden, D. T., & Long, K. (2011). Music Marketing: A History and Landscape. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(2), 120 - 125.

Rosario, A. B., Sotgiu, F., De Valck, K., & Bijmolt, T. H. A. (2016). The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales: A Meta-Analytic Review of Platform, Product, and Metric Factors. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 53(3), 297 – 347.

Schwedel, H. (2018, September 4). A Guide to TikTok for Anyone Who Isn't a Teen. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://slate.com/technology/2018/09/tiktok-app-musically-guide.html

Shotwell, J. (2019, April 18). Major Labels Demanding 'Guaranteed Money' From TikTok Owners. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2019/04/major- labels-demanding-guaranteed-money-from-tiktok-owners.html

Simon, R. (2006), “Social broadcasting”, Billboard, Vol. 118 No. 38, p. 6.

Stevens, R. E., Loudon, D. L., & Wrenn, B. (2006). Marketing planning guide. Psychology Press.

Stratton, J. (1982). Between Two Worlds: Art and Commercialism in the Record Industry. Sociological Review, 30(2), 267 - 285.

Taylor, D., Lewin, J., & Strutton, D. (2011). Friends, fans, and followers: do ads work on social networks? How gender and age shape receptivity. Journal of Advertising Research, 51(1), 258–275.

Thall, P. M. (2002). What They'll Never Tell You About the Music Business: The Myths, the Secrets, the Lies (& a Few Truths). New York: Watson-Guptill Pub.

Turner, G. (2013). Understanding celebrity. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

Wallace, E., Buil, I., & de Chernatony, L. (2017). Consumers' selfcongruence with a "liked" brand cognitive network influence and brand outcomes. European Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 367–390.

Yeung, P. (2019, July 30). TikTok is Changing the Music Industry. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from http://ffwd.medium.com/tiktok-is-changing-the-music-industry-bc19a8468b61

Yurieff, K. (2020, February 21). How TikTok became a hitmaker for the music industry. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from http://www.cnn.com/2020/02/21/tech/tiktok-break-my- stride/index.html

Zorn, E. (2018, September 3). But Will She Ever Sing at Carnegie Mall? Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1987-08-02-8702260246-story.html